|

|

|

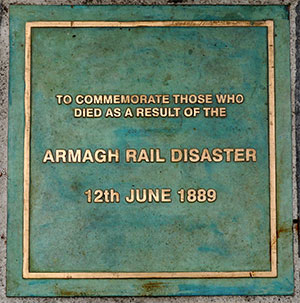

Memorial to those who lost their lives in the Armagh Rail Disaster Located at the West end of The Mall, Armagh City, Co. Armagh. © 2014 Sinton Family Trees |

|

|

The following is from http://www.copyrightservice.co.uk/copyright/p01_uk_copyright_law

Crown Copyright Crown copyright will exist in works made by an officer of the Crown, this includes items such as legislation and documents and reports produced by government bodies. Crown Copyright will last for a period of 125 years from the end of the calendar year in which the work was made. If the work was commercially published within 75 years of the end of the calendar year in which it was made, Crown copyright will last for 50 years from the end of the calendar year in which it was published. As this report was published and delivered to the Company on the 7th November 1889, I believe the third paragraph pertains and the copyright has therefore expired.

This transcription and map are © 2002 - 2026 Sinton Family Trees

|

|

The grave locations for 33 of the victims who are buried in Armagh Parish Church (St. Mark's) can be seen in a series of Google maps at St. Mark's Index The grave locations for 2 of the victims who are buried in St. Aidan's Parish Church, Salters Grange can be seen in a series of Google maps at St. Aidan's Index |

|

GREAT NORTHERN RAILWAY OF IRELAND.

Board of Trade, (Railway Department.)

SIR,

1, Whitehall, London, S.W., 8th July 1889.

I HAVE the honour to report, for the information of the Board of Trade, in compliance with the Order of the 13th ultimo, the result of my enquiry into the causes of the very terrible collision which occurred on the 12th ultimo near Armagh station on the Newry and Armagh branch of the Great Northern Railway of Ireland.

In this case a heavily laden excursion train of Sunday school children and others, consisting of engine, tender, and 15 vehicles, including a brake van in front and a brake carriage in rear, fitted throughout with the non-automatic vacuum brake, due to leave Armagh for Warrenpoint at 10 a.m., failed quite to reach the top of the rising gradients of 1 in 82 and 1 in 75 which commence about 0.29 mile (466.7 metres) from the buffer stops at the end of the platform of the Newry and Armagh station at Armagh, and extend for 3.15 miles (5 kilometres) ; the train was then divided between the fifth and sixth vehicles from the engine to enable it to be taken on in two portions, but the rear 10 vehicles, having been inadequately secured, ran back towards Armagh and met at a high rate of speed-about 1½ miles (2.4 kilometres) from the spot from which they had commenced to move backwards - the 10.35 a.m. ordinary passenger train from Armagh, which had started about 20 minutes after the excursion train and was being stopped, although it was still running at a speed of (probably) about five miles (8 kilometres) an hour, when the collision took place. The effects of the collision were most disastrous, the rear three vehicles of the excursion train being completely destroyed, their debris being thrown principally to the right of the direction in which they had been running, down the slope of an embankment about 46½ feet (14.1732 metres) high on which the railway is here carried. On the collision occurring, the engine of the ordinary train-which consisted of engine and tender, horse box, brake van, three carriages, and third clam brake van, fitted with the non-automatic vacuum brake-was separated from its tender and thrown over to the right upon its right side (left wheels uppermost) on to the top of the slope of the embankment. The rear five vehicles broke away from the horse box, ran back down the incline, and were stopped by the guard in the rear brake van applying his hand brake after they had run back about a quarter of a mile. The tender and horse box also ran back and were stopped by the driver-who, upon the crash occurring had turned round and was holding on by the tender coal plate-applying the tender hand brake (which had remained in working order) a few carriage lengths short of the rear five vehicles. Up to the present time no less than 78 deaths of passengers (of whom 22 were 15 years of age and under) in the excursion train have taken place, and in addition to these, 260 passengers (of whom about one-third are 15 years old and under) are returned as having been more or less seriously injured. Two passengers (of whom there were 14) in the ordinary train have complained of slight injury. The rear guard of the excursion train and the fireman of the ordinary train were injured, the former having had a marvelous escape. A list of the deceased passengers, the composition of the excursion train, and a list of the damage to rolling stock are given in an Appendix. |

| D E S C R I P T I O N |

|

The Newry and Armagh line was opened as a separate undertaking in August 1864, and was absorbed by the Great Northern Railway Company in 1879. It is a single line 21 miles (33.6 kilometres) long, worked on the train staff and ticket system, the train staff stations being Newry, Goragh Wood, Market Hill, and Armagh. There is an intermediate station, not a staff station, between Market Hill and Armagh, called Hamilton's Bawn, nearly five miles from Armagh. At the time the line was opened, the block system had not been made a requirement in the working of new lines, and it has not hitherto been introduced on this line.

The gradients, &c. of the line between Armagh and Hamilton's Bawn, commencing at the buffer stops at the end of the Newry and Armagh platform at Armagh, are as follows : |

| Horizontal | 0.29 | miles | 446.7 | metres |

| Rising 1 in 82 | 0.66 | miles | 1,062.0 | metres |

| Rising 1 in 75 ¹ | 2.49 | miles | 4,007.0 | metres |

| Horizontal | 0.03 | miles | 48.3 | metres |

| Falling 1 in 80 | 0.90 | miles | 1,448.0 | metres |

| Falling I in 800 | 0.25 | miles | 402.3 | metres |

| Falling 1 in 85 | 0.26 | miles | 418.4 | metres |

| Horizontal | 0.03 | miles | 48.3 | metres |

| Hamilton's Bawn Station | 4.91 | miles | 7,902.0 | metres |

| The curves and straight portions between the two stations are as follows, commencing again at the buffer stops at Armagh : |

| Straight | 0.06 | miles | 96.6 | metres |

| Curve to left, 1 mile radius | 0.07 | " | 112.7 | metres |

| Curve to right, 0.18 mile radius | 0.07 | " | 112.7 | metres |

| Curve to right, 0.22 mile radius | 0.09 | " | 114.8 | metres |

| Straight | 0.17 | " | 273.6 | metres |

| Curve to right, 1 mile radius | 0.14 | " | 225.3 | metres |

| Straight | 0.30 | " | 482.8 | metres |

| Curve to left, 1 mile radius | 0.30 | " | 482.8 | metres |

| Curve to right, 1 mile radius | 0.27 | " | 434.5 | metres |

| Straight | 0.21 | " | 338.0 | metres |

| Curve to right, 1 mile radius ² | 0.53 | " | 853.0 | metres |

| Straight | 0.71 | " | 1,143.0 | metres |

| Curve to left, 1 mile radius ³ | 0.49 | " | 788.6 | metres |

| Straight | 0.58 | " | 933.4 | metres |

| Curve to right, 1 mile radius | 0.72 | " | 1,159.0 | metres |

| Curve to left, 1 mile radius | 0.20 | " | 321.9 | metres |

| Hamilton's Bawn Station | 4.91 | miles | 7,902.0 | metres |

|

¹ The train stopped 0.12 mile (193.1 metres), and the collision occurred 1.62 miles (2607 metres) from the termination of this gradient. ² The collision occurred 0.39 miles (627.6 metres) from the end of this curve. ³ The train stopped 0.09 mile (144.8 metres) from the end of this curve. |

|

The excursion train came to a stand about 0.12 mile (193.1 metres) from the top of the rising gradient of 1 in 75 or 3.32 miles (5,343 metres) from the buffer stops at Armagh and near the termination of the curve to the left of 1 mile radius and 0.49 miles (788.4 metres) long. The collision occurred on the gradient of 1 in 75, as nearly as possible 1.5 miles (2,414 metres) from where the vehicles commenced to run back, or 1.82 miles 2,929 metres) from the buffer stops at Armagh Station. The line at this place is carried on a high embankment about 46½ feet (14.1732 metres) high, on the Newry side of which there is a deep cutting and a curve to the right ; and it was in this cutting when, as nearly as could be judged, some 500 yards (457.2 metres) off that the runaway portion of the excursion train was seen from the engine of the ordinary train, the collision occurring after the ordinary train (the speed of which had been reduced from about 25 miles to five miles an hour on collision) had run about 100 yards (91.44 metres), while the runaway vehicles had passed over a distance of about 400 yards(365.76 metres).

|

| E V I D E N C E |

|

1. Patrick Murphy, driver ; 31 years' service, 20 years driver ; with the Newry and Armagh Company until 1879, when the line was purchased by the Great Northern Company. I have been driver since 1869 on the Newry and Armagh Railway. I commenced work at 8 a.m. on the 12th June, and brought in the 8.40 a.m. train from Newry to Armagh, where I arrived at 9.50 a.m. The rails were dry on the incline leading to Armagh. I started back for Newry at 10.39 a.m., four minutes late, waiting for the arrival of a train from Belfast. My engine was No. 9, a six-wheeled engine, with the leading and driving wheels coupled, and a six-wheeled tender. The train consisted of a horse-box, brake-van, three carriages and a brake-van with a third class compartment. The vacuum brake was fitted to the four coupled wheels of the engine, to all the wheels of the tender, and to four out of six wheels of the rear five vehicles, there being pipes under the horse-box. I tested the brake before I started, and could get about 20 inches of vacuum. There were about 20 passengers in my train. I had the train staff on the engine. Nothing unusual occurred on the journey until the fireman, who was on the right hand side of the engine, called out " Hold ! hold ! hold ! " this was near the nineteenth mile post (i.e., two miles from Armagh), and my speed at the time was from 25 to 30 miles an hour. I first whistled, then shut off steam on myself seeing the carriages coming back, next applied the vacuum brake with full force; the fireman reversed and applied back steam. By these means the speed was reduced to between two and three miles an hour, when the carriages, of which the speed was high, ran into the engine. I did not jump off, but turned round and caught hold of the coal plate of the tender, standing on the tender foot-plate ; the tender at once broke away from the engine, and ran back with the horse-box attached to it for about a quarter of a mile, when I stopped them with the tender brake which was still working. The five vehicles had broken away from the horse-box and ran back in front of the tender and horse-box, and were stopped by the guard's brake three or four carriages' lengths from the horsebox. On the collision taking place, the engine turned over on its right side, and remained with its right side lying on the slope of the bank, just foul of the nearest rail. The tender gave a great lurch on the engine breaking away from it, but did not leave the rails. The fireman jumped off to the right just before the crash, and rolled down the slope of the bank ; not much of the debris of the runaway vehicles came on to the footplate, and the wreckage went principally to the left. I did not look at my watch when the accident occurred, but it must have been about five minutes after starting. The morning was fine and dry. I have driven No. 30 engine, which is a sister engine to No. 86, the one which drew the excursion train. I have never taken more than 10 vehicles up the Armagh Bank with it. With No. 9 engine, I have taken a train of 17 vehicles, consisting of five carriages and 12 cattle wagons and horse-boxes. I had seen the excursion train start, and thought it was a heavy train, and passed the remark to my fireman that I thought our engine could pull it up the bank. I have taken excursion trains myself, consisting of 14 vehicles with engine No. 82A, which is a heavy engine ; I never stuck on the Armagh Bank. On the runaway carriages colliding with the engine it stopped dead and quivered, but did not run back at all before turning over.

2. William Herd, fireman, 14 years' service, eight years' fireman. I have been working all the time on the Newry and Armagh line. I have been with Murphy six or seven years. I started with the 10.35 a.m. train from Armagh for Newry on the 12th June, my place being on the right side of the engine. We started about four minutes late. Nothing unusual took place till near the 19th mile post, and when running at a speed of between 20 and 30 miles an hour, I caught sight of something coming back in the - cutting. Upon seeing this I called out to the driver, " Hold." He opened the whistle, shut off steam, came to my side to see whet it was, then applied the vacuum-brake with full force. I reversed the engine and applied steam when the driver was on my side, and before he applied the vacuum-brake; the sandboxes were not opened. The speed was reduced to less than five miles an hour when the crash took place, just before which I jumped off to the right and rolled down the bank, spraining my ankle a little. Not much of the wreckage came down on my side. I thought at first it was the whole train coming back. The speed seemed very high. The morning was fine and dry at this time. Murphy passed the remark to me before the excursion train started that it was a heavy train, but he thought our engine could take it up the bank. 3. Daniel Graham, guard ; 29 years' service ; guard 25 years.' in the first instance, with the Newry and Armagh Company, and since with the Great Northern Company. I was guard of the 10.35 a.m. train from Armagh to Newry on the 12th June. The train consisted of engine, tender, horse-box, guard's van, three carriages, and a third-class brake carriage, six in all. The vacuum-brake was fitted throughout, except to the horse-box, which had a pipe only. We started at 10.38 a.m., three minutes late, waiting for some luggage from a Belfast train due at 10.21 a.m. I was in the rear brake carriage. The first intimation I had of anything unusual was from the driver whistling, about the over bridge near the 19¾ mile post, the speed being about 20 miles an hour at the time. I applied my band-brake at once, but I think the vacuum-brake was on before I did so, and I was merely able to take an extra turn or two to the brake wheel. I then looked out on the left side of the brake-carriage, saw some vehicles coming back, and saw one person jump out, and then came the crash, which knocked me down senseless for a few seconds. When I recovered my senses, I found my brake-carriage was running back down the incline, at a speed of perhaps five miles an hour. I at once applied the hand-brake and stopped the train a short distance on the Newry side of the over-bridge. The tender and horse-box were separated from the rest of the train, and stopped three or four carriage length from the front vehicle. I do not know what time the collision occurred. I was able to give assistance afterwards to the injured, and have not had to go on the sick list. 4. Thomas McGrath, driver ; 13 years' service, two, years driver, six years fireman ; all the time in the Great Northern Company's service. I commenced work on the 12th June at, 5.30 a.m., with engine No. 86, a six-wheeled engine, with the driving and traiIing-wheels coupled, with inside cylinders, and a six-wheeled tender. The engine is fitted with the vacuum-brake, working blocks on each of the driving and trailing-wheels, and on each of the tender-wheels. I am a spare driver, and work different engines, according to circumstances, and have worked No. 86 engine some two dozen times. My first work was to bring down the train of empty carriages, which afterwards formed the excursion train, from Dundalk. I started at 6.40 a.m., and arrived at Armagh at 8.35 a.m. ; I turned the engine, got water, and then waited for the train to start at 10.0 a.m. After turning and getting to the Newry end of the train, I put 13 vehicles on the up-platform main line, and a brake-van and carriage on the down-platform line ; when these latter were loaded, I crossed the road with them, and took up seven of the 13 vehicles which mere on the up-platform line; I pulled up with these nine vehicles about 100 yards, crossed with them into the Newry and Armagh yard, pulled forward on the Newry and Armagh main line to allow room for the remaining six-vehicles to be attached to the rear of the train ; these six vehicles were then moved on to the Newry and Armagh line, and I then backed on to them. When the train was ready to start, it consisted of engine and tender, brake-van 13 carriages and a brake-van or carriage, 15 vehicles in all. The brake power consisted of the vacuum brake, applying to the engine and tender, and to four wheels on each of the vehicles composing the train. The train then started at about 10.15 a.m. with a guard, front and rear. I had never been a driver on the Newry and Armagh line previously, but I had been a fireman on it with a ballast train, about five years ago, for six months, and on excursion trains for three years in succession, the last year being 1886, since which time I have not been on the line between Armagh and Goragh Wood. On finding that my train was to consist of 15 vehicles, I informed the station-master that I should not be able to take them, as I had got instructions at Dundalk that there would be only 13. The station-master replied " I did not write those instructions for you " ; I said " Mr. Cowan wrote: them." The stationmaster then said " Any driver that comes here does not grumble about taking an excursion train with him." I replied "Why did you not send proper word to Dundalk, and I should have a proper six-wheel coupled engine with me." I said no more, but walked away down the platform, this was about 10 minutes before the train started. I had great confidence in the engine I had, and thought I should be able to get up the bank with the 15 vehicles. We then started with about 130 lbs. (8.963 bar) of steam, the blowing off point, and we got on slowly till near to the top of the bank, not more than a few yards from it, gradually losing speed the whole way, but having still 125 lbs. (8.618 bar) of steam when the engine stopped. I made no attempt to start after the train stopped, feeling it would be useless. We had stopped two or three minutes, when Mr. Elliott, Mr. Cowans' chief clerk, who was on the foot-plate, said he would divide the train ; to which I said " All right.." Mr. Elliott then went away to the rear brake-van, and I saw him standing on the step of the rear van before the train was divided, and I saw also assistant-guard Moorhead putting down stones under the wheels of the rear vehicles, on the left side, also before the train was divided. Moorhead then came running to me and said " Hamilton's Bawn " ; this was after he had uncoupled the train, before which I had not set back. I had felt the pulling asunder of the brake-pipes when Moorhead uncoupled them, and my engine went back about a foot or so ; I think the screw-coupling must have been released before the brake-pipes were detached. Immediately after this, I heard Mr. Elliott shouting "Slack up " meaning that I should set back on the rear of the train. I looked back, and did so, Moorhead going back to hook-on, but in doing so he fell down on the side of the line ; on recovering himself, he ran on towards Armagh, I still following down, but Moorhead could not overtake the rear portion of the train, which ran away from him altogether, Mr. Elliott being on the step of one of the carriages. I followed the runaway part of the train, and was about a quarter of a mile from it when the collision took place. I had kept it in view till just the last. I do not think its speed ever exceeded 30 miles (48 kilometres) an hour. I did not see anyone jump from the runaway carriages as they were going down. Mr. Elliott was the first person to suggest dividing the train. I did not object, thinking the rear brake-ran would hold the rear portion. I am sure the stones were put down before the train was divided. I saw no one go back to protect the rear of the train, but supposed the guard would have done so. I knew the regular train was due to leave Armagh at 10.35. I do not think my speed, on ascending the bank, ever exceeded five or six miles (9.6 kilometres) an hour. It was about 10.35 a.m. when we stopped, up to which time the speed had been gradually decreasing. I think my engine would have mastered 13 vehicles well. I cannot account for the rear vehicles running back, except from the weight of the train on the rear van. By the Company's Officers. - I was doubtful about my engine being able to take 15 vehicles up the bank. I did not ask for any assistance. Mr. Elliott asked me if I wanted assistance, and I said, " I think my engine will take them up." I had brought 14 empty vehicles from Dundalk to Portadown, and a 15th was put on at Portadown. 5. Henry Parkinson, fireman ; three years' service ; nine months fireman. I am McGrath's regular fireman. I was firemen of No. 86 engine, and brought the empty train from Dundalk to Armagh on the 12th June. We had 14 vehicles from Dundalk, and took on a 15th at Portadown, and reached Armagh about 8.40 a.m. The train was ready about 10.15 a.m., and it then started, consisting of 13 vehicles, a brake-van next the engine, and a brake-van or carriage at the rear of the train, with a guard in each brake. Mr. Elliott was on the footplate, with me and McGrath. Before starting, McGrath spoke to the station-master, and said that he had instructions from Mr. Cowan to take only 13 carriages. The stationmaster said there would be 15, as there were too many passengers for 13. McGrath said if there were 15 he must have an assistant engine to help him up the bank. The station-master said he had no assistant engine. Some further conversation passed on the subject, but it ended by McGrath starting with the 15 vehicles. Before this a shunter had told McGrath that some of the carriages were to be taken by the regular train at 10.35 a.m. I do not know why this arrangement fell through. After starting we got on pretty well at first, but about two miles (3.2 kilometres) from Armagh the speed gradually became less, and at last we stopped altogether a short distance from the bridge at the top of the bank. We had about 125 lbs. (8.618 bar) of steam on starting, and about the same when we stopped. The only reason I could see for our stopping was the curve in the line. I then had some duties to attend to which prevented my hearing what passed between Mr. Elliott and McGrath. On coming back to the footplate, I found that Mr. Elliott had gone, and McGrath told me that the train had been divided, and that the rear portion was running away. Before this I had not heard Moorhead say to the driver " Hamilton's Bawn." McGrath then followed the rear portion of the train down the incline, and stopped about a quarter of a mile from the point of collision. 6. William Moorhead, porter ; six years' service. Watchman at Newry four years and a half. One year and a half porter. I commenced work on the 12th June at Newry about 8.15 a.m., and came in the van by regular train to Armagh. I had left duty on the 11th at 8.15 p.m., after 12 hours' duty, with an hour off for dinner. I have acted as assistant guard about twelve times between Newry and Armagh ; and on the 12th June I was sent from Newry to assist on the excursion train from Armagh to Warrenpoint and back. Mr. Elliott instructed me to go in the front brake-van from Armagh, as assistant guard. I accordingly went in the front van, in which there were eight soldiers and two civilians with me. I think the train started about 10.15 a.m. The train mounted the bank slowly, not exceeding eight miles (12.8 kilometres) an hour, and this gradually diminished till we stopped near the top of the bank, just before this there having been a little rain. I do not know if the steam had sunk down. I put on my brake when the train stopped, and remained in the van for a few minutes, and I then saw Mr. Elliott near the rear van speaking to the rear-guard. He then came back to about the fifth carriage and waved to me. I went down to him, and he said he was going to cut the train. He asked me how many carriages Hamilton's Bawn siding would hold. I told him I was not sure, as I did not know how many wagons were in it, but that it might hold five. He then told me to unhook at the rear of the fifth vehicle, and gave me the same instructions a second time. I got in between the fifth and sixth vehicles, and first uncoupled the vacuum pipes and put them on the stops. No movement of either portion of the train took place on my doing this. I then unhooked the two side chains, and then unscrewed the screw coupling, it being sufficiently slack for me to do so, and lifted the shackle off the rear hook of the fifth vehicle. Before unscrewing I had put in one small stone behind the front left wheel of the sixth vehicle. Mr. Elliott then told me to go ahead gently to Hamilton's Bawn, and hurry back with the engine if the siding would hold all five vehicles. I went up to the driver on the left side, and said " Hamilton's Bawn, go ahead gently." I then jumped into the van, took off the brake, and felt my van coming back 12 or 18 inches (30 or 45 centimetres), which I thought was from the driver setting back before starting, and it must have been this backward movement that set the rear portion of the train in motion, as it had been quite steady all this time. I looked out to see what had happened, and I saw the rear portion beginning to move back. Mr. Elliott signaled to me to come back, upon which I told the driver that the rear part was running back, and asked him to come back gently, so that I might hook on again. The driver, who was just moving ahead, stopped. I then jumped down on the left side, and ran towards Armagh, and tumbled down twice (there being some rails on the ground) on my way, and never succeeded in reaching the sixth vehicle, the speed of the rear portion increasing as I followed it. The front portion of the train passed me, and I tried to get on, but could not succeed, and I followed the train on till I came to where the collision took place, passing the front portion of the train a short distance from it. I do not know what Mr. Elliott had done to prevent the rear portion of the train from running back, except that I supposed the rear guard's brake had been put on. I did not make any objection when Mr. Elliott directed me to uncouple. I have never before acted as guard with so heavy an excursion train, nor when a train has been divided on the bank. 7. Thomas Henry (examined in hospital), porter at Dundalk, and acting occasionally as relieving guard, nine years' service ; acting as relieving guard for three years, and sometimes before that when acting as shunter. I came on duty at 6 a.m. on the 12th June, having been on duty the previous day from 8 a.m. till 1.30 p.m., with an interval of an hour for dinner. I left Dundalk at 6.40 a.m. on the 12th with an engine and 14 vehicles to form the excursion train from Armagh to Warrenpoint. We went via Portadown, where we put on an extra carriage by direction of the station-master. The train reached Armagh at 8.45 a.m., and there a first class carriage was substituted for the third class, which had been put on at Portadown. At first McGrath told the station-master he would be unable to take more than 13 vehicles up the bank, but I have no personal knowledge of anything that passed as to assisting the train up the bank. I had received instructions from Mr. Cowan's office on the previous evening to take charge of the train from Dundalk till it got back. The train was ready to start about 10.15, and I took my place in the rear van, which consisted of three compartments, one for passengers, one for luggage, and one for me. There was a hand-brake on the van, which I had no occasion to use at all till the train stopped on the bank, and I had no knowledge whether it was in good working order. In my compartment and the luggage compartment there were about 14 or 15 persons, two of whom were children, and there were about 20 in the other compartment. There were a few baskets of provisions. The train started all right, and attained a speed of about 15 miles (24 kilometres) an hour, which gradually diminished till we stopped near the top of the bank. I put on my hand-brake as soon as the train stopped, and I did not notice the vacuum brake applied. Mr. Elliott then came down in about three minutes, and told me to apply my brake, which I told him I had already done. He then told me to get out and scotch the wheels with stones. I did so: and had put one stone under each of the six van wheels, and also under the three right wheels of the vehicle in front of the van, and as I was putting down the last stone, I felt the carriages coming back. I went on the van, and got in, and tried, with the assistance of two passengers to get an extra turn at the brake handle, and was still doing this when Mr. Elliott jumped up on the left step, and said try and make the best you can without breaking it (meaning the brake handle), and I said I could make no more. He then said, " Oh, my God, we will be all killed," and jumped off. The speed then gradually increased, till it became so fast we could not see the hedges as we passed. I was still in the van when the crash took place. I had not seen the engine of the regular train till we came on to it. I remember no more till I came to my senses in the infirmary. Mr. Elliott did not tell me he was going to divide the train, but I suspected it. I had intended to go back after scotching the wheels; I had flags and fog signals with me for the purpose. I saw one man jump from the van, he was not killed. I had nothing to do with locking the doors before the train left Armagh. I had locked the right-hand doors at Dundalk, and these had remained locked till the train reached Armagh, and what was done afterwards was the act of the station officials after checking tickets. There was a countryman putting stones under the heels after the train had begun to move back; this moving back must have been caused by the engine slacking back to ease off the coupling. I could make nothing more of the brake than I did at first, even with the assistance of the two other men. 8. James Elliott (examined in prison), 23 years' service : I was first an office boy in the service of the Dublin and Belfast Junction Railway Company ; I was then gradually promoted from step to step in the office at Dundalk, and when the Great Northern Company took the line, I was second clerk in the general manager's office at Dundalk. I succeeded to my present post of chief clerk about 10 years since. Almost every other day during the summer months of these 10 years I have had charge of excursion trains to various places accompanying them out and home. Sometimes one and sometimes three times in each summer I have had charge of excursion trains from Armagh to Warrenpoint, and also from other stations on the Newry and Armagh line. I have had, I think, as large, or almost as large, a number of excursionists as on the present occasion, and as many as 16 or 17 vehicles between Armagh and Warrenpoint. This would be three or four years since, when the engine would have been a six-wheels coupled engine. I believe the application on this occasion was for a train of 14 vehicles, the engine power being left to the locomotive department. I arrived at Armagh at about 9.50 a.m. on the 12th June, and I then found the whole train, consisting of 13 carriages and two vans, standing at the up main line platform for Clones ; the train was then loaded, with the engine at the Goragh Wood end. I walked along the train, and saw that it was well filled with children and adults all mixed together, and some people still getting in. I noticed that the checkers were locking the doors on the right hand side of the train, as it would proceed to Goragh Wood. This is usually done with excursion trains, to prevent unauthorised persons getting in after the tickets are checked. Coming back from the rear of the train, I met Mr. Foster, the station-master, and I said the train seems pretty well filled ; he said, " Yes, I had to give out more tickets this morning, and I wanted to put on more carriages, and the driver refused to take them." I said I thought he would be the better of assistance for what he has got, and Mr. Foster at once sent shunter Hutchinson to tell driver Murphy to lie ready to assist the excursion train up the bank. I shortly after went and asked McGrath if he wanted assistance, and he said he did not. I knew that he had a four-wheel coupled-engine on his train, and though I thought he had his load, I did not press him to have assistance, thinking he was a better judge than me of the power of his engine. I do not know that I have had any previous experience of the power of an engine like No. 86 for drawing a heavy train up the Armagh bank ; but two years ago, I think, a bogie-engine, No. 19, four-wheels coupled, took up an excursion train of 14 vehicles without any special difficulty. Some shunting had to take place to get the train on to the Newry line, and we were able to start at 10.15 a.m. by my watch. I rode on the engine, McGrath and Parkinson being the only other persons on it ; they appeared both fit for their work, with no appearance about them of having taken liquor. It is my usual custom with these excursion trains to travel on the engine, there being-a guard in each of the vans, the rear guard, Henry, being in immediate charge. I considered Henry an experienced man, as though not a regular guard, he is constantly acting as guard, particularly with special trains. Moorhead has also acted as special guard with cattle and other trains, but he is not a regular guard. The train made a good start, with, I think, 130 lbs. (8.963 bar) of steam. I did not see the vacuum brake tried. The engine did very well till it passed Derry's crossing (near the nineteenth mile post) where it began to lose speed, without any apparent cause, and continued to do pretty well till it had got to within 300 or 400 yards (274.32 or 365.76 metres) of where it stopped, and then the speed gradually diminished till the engine stopped about 200 yards (182.88 metres) from Dobbins Bridge, at 10.33 a.m. by my watch, the pressure being just below the mark which, I believe, represents 125 lbs. (8.618 bar) I do not think the driver applied the vacuum brake when we stopped, but he may have done so without my noticing it. I consulted the driver as to what was best to be done, and he said I will take a portion of the train to Hamilton's Bawn, and return for, the remainder. I thought this was the best thing to be done, as Hamilton's Bawn was only about a mile off. I then at once went along to the rear van and said to Henry, put on your brake tight, he said, " it is on." I asked if he had any sprags, he said he had not. It was not his duty to have them in a passenger train van, but I thought he might have had some. I then said, " put some stones behind the wheels as we are going to take a portion of the train to Hamilton's Bawn," and I saw Henry come out of the van on the left side, the side I was on. I then ran back to the front of the train, called Moorhead, and asked him how many carriages Hamilton's Bawn siding would hold ; he said, five, he thought, but he had noticed two wagons standing there when he passed in the morning. I said take five with you, and if there is not room, bring the front van back. I then told him to uncouple the train between the fifth and sixth vehicles. I did not see him put a stone under the front wheel of the sixth vehicle ; he first uncoupled the left side chain, then the vacuum pipes, and then either the screw coupling or right side chain, I cannot say which he did first. At first he could not get off the screw coupling by easing the screw a little, and I then made him unscrew to the full length, and he was then able to get the coupling off without much difficulty, and without the engine being set back, it being my object to prevent this by letting Moorhead unscrew to the full extent. After the severance had been made, both portions of the train remained at perfect rest ; I then told Moorhead to tell the driver to go straight away and on no account to come back against the carriages, and he went up to the driver ; I then went down towards the rear van for the purpose of myself going towards Armagh with signals to protect the train, and I had almost got to the van when I saw the buffers driven in and heard the grinding of the carriages going over the stones, and I made up my mind that the driver must have set back against the rear portion of the train. The van began to move back also when the pressure from the buffers came against it. I at once tried to put stones behind the wheels, and put down three or four, but they were simply crushed by the wheels, and I then jumped on to the left step of the van of which I noticed the wheels revolving, and not skidding at all, and shouted to Henry to put on the brake tightly. He said he could make nothing more of it. I saw that he and another man were both working at the handle. The speed by this time had reached 20 miles (32 kilometres) an hour. I jumped off the van, and fell down, and ran up towards the driver, who was coming down after the train. I said, "My God ! what did you come back against the carriages for ? " And he said he could not get started, and set, back the slightest thing. I then got on the engine and followed the runaways down until stopped by the gateman at Derry crossing, and I neither saw nor heard the collision. I calculated that, I should save time by dividing the train, instead of waiting to be assisted by the regular train. From what I saw I believe the brake of the rear van must have been out of order. After the carriages started I saw two or three men about the line, putting down stones. I saw no pieces of wood lying about to use as sprags, and it did not occur to me to try and use the old rails. I was fully under the impression that the van break would hold the train, otherwise I would not have divided it. 9. James Park, locomotive superintendent of the Great Northern Railway of Ireland, stationed at, Dundalk. I was informed of the collision at Armagh at 11.49 a.m. on the 12th June,and I proceeded to Armagh via Portadown at 12.10 p.m. with a break down train. I arrived at the scene of the accident at 2.10 p.m. and found that the tender and whole of the 10.35 a.m. train had arrived in Armagh Station. The tender was slightly damaged, but none of the vehicles, and I heard from the guard that a horse in the box next to the tender was not injured. I first found the engine of the 10.35 a.m. train lying on the right slope of the bank on its right side, left wheels uppermost, foul of the right rail. The third carriage from the rear of the excursion train was lying on the main-line alongside the engine on its floor, with its Armagh end on the ballast, and its other end tilted up on its wheels, which remained in the axle-boxes. The roof of this carriage was still in position, but the compartments were all swept away with the exception of the end one next Goragh Wood. The fourth carriage from the rear was off the rails, with its body nearly intact, on its wheels with another pair of wheels (probably from the third carriage) under its trailing headstock. The fifth carriage from the rear was off the rails, with its wheels between rails which had spread, one quarter-light broken. The sixth carriage from the rear (a first-class) was in a similar position to the fifth, and not damaged. The seventh carriage from the rear had one trailing-wheel off the rails, one window broken, and the back rail of seat broken. The three remaining vehicles were on the road, and undamaged. All the couplings remained undamaged and tight, except those of the two destroyed. The first and second vehicles from the rear were completely destroyed and the wheels shot down the bank on left side. No vehicles seem to have got past the engine of the 10.35 a.m. train. Engine No. 86 was, in my opinion, fully equal to take a train of 13 loaded vehicles between Armagh and Newry. It is one of the largest of this type of engine in the Great Northern Company's service. I was not at Dundalk when the special train was ordered, nor did I know anything of its running till the accident was reported to me shortly after its occurrence. In my absence the whole of the arrangements were made by running shed foreman William Fenton, who has occupied that position at Dundalk during the 8½ years I have been there. 10. John Foster, station-master, at Armagh ; 35 years' service; 12 years station-master at Armagh. I was on duty on the morning of the 12th June, and had charge of the arrangements connected with the excursion train for Newry, due to start at 10 o'clock with about 940 passengers, children and adults. To hold these, there were required 13 vehicles and two brake-vans, one of which, the rear one, had one passenger compartment. From my knowledge of the traffic, I considered that engine No. 86 was quite well able to take these 15 vehicles up the Armagh Bank. On McGrath's arrival from Dundalk with the empty train, I was going to make his train up to 16 or 17, but he declined to take more than the 15 he had brought from Dundalk, and I told the shunter to give him no more. It had not been at all in my mind to transfer any of the 15 vehicles to the 10.35 a.m. ordinary train. On the arrival of the empty train I had instructed the shunter to attach a first-class carriage to it, but, on the shunter proceeding to do this, McGrath objected to its being added to the 15, so the rear third-class carriage from Portadown was removed, and the first-class substituted for it. The train started at 10.16 a.m., with a train ticket, full throughout, and the 10.35 a.m. train followed with the staff. Mr. Elliott, after going round the train, said it had better be assisted up the bank, upon which I gave the driver of the 10.35 a.m. train instructions, through the shunter, to be ready to do so : but two minutes before the train started, Mr. Elliott told me that he had been speaking to McGrath, who said that he did not want assistance. There was a very slight shower shortly after the train started. I have no knowledge as to the cause of the engine of the excursion train stopping where it did. I could not say whether the doors of the excursion train were locked on both sides from my own knowledge, but I do know that the manager of the excursion train desired that this should be done. It is a common practice to do this with children's excursion trains. I cannot speak positively as to the number of passengers in the train, but it could not be more than 941, and of these, roughly speaking, two-thirds would be children up to 15 years of age, and one-third adults. I think that, of the 600 children, or thereabouts, 150 would be under five years of age. The line is worked on the train staff and ticket system, Market Hill being the first staff station, 10 minutes being the interval for one passenger train following another, 20 minutes for a passenger train following a goods' train, and five minutes for a goods train following passenger train. I gave the driver, McGrath, the ticket, and I had the staff in my hand a second before this. I think I have sent as many, if not more, vehicles than 15 in previous excursion trains, but this would have been with a sixwheel coupled engine ; but I could not be certain of the greatest number there have been taken by a fourwheel coupled engine, though I am pretty sure that 12 carriages filled with police and two vans have been taken from Armagh towards Newry by a four-wheel coupled engine. I remember one case of an engine failing to draw its train up Armagh Bank, and then it came back altogether. This was a train of 18 wagons of cattle drawn by a single engine. 11. Robert Ballantyne, platform porter ; five years' service; all the time at Armagh. On the morning of the 12th June, I was asked by Mr. Pixon, one of the superintendents of the Sunday school excursion, to lock the doors of the carriages after checking the tickets, to prevent people getting in who had no tickets. I accordingly locked then on the right side, but I cannot say whether they were locked on the left side. They were not locked by me or the other man, who was checking tickets. There was sitting room for all I saw ; fourteen or fifteen was the largest number I saw in any compartment. 12. James Hutchinson, shunter ; 14 years' service ; all the time shunter at Armagh : I was engaged making up the excursion train on the 12th June. I heard McGrath tell Mr. Foster, the station-master, that, if he put on any more carriages than what he had, he might send for another engine. Mr. Foster told me to put on no more. I had been going to put on two more, as there seemed to be want of room. When Mr. Elliott came, he went along the carriages, and seeing them so thronged, he said to Mr. Foster that they would be the better of a shove up the bank, so Mr. Foster told me to get Murphy's engine ready, I accordingly went to Murphy and told him, and he was prepared to push the excursion train when it started. Mr. Elliott then went to McGrath and asked him if he wanted a shove up the bank, and he said he did not, and I then told Murphy he would not be required. I have seen as many carriages and wagons before taken up by a similar engine, but not so many carriages only that I remember. I had no misgivings in my own mind its to the engine taking the carriages up on this occasion. 13. Thomas McShane, carriage examiner ; 27 years' service, 19 years carriage examiner at Dundalk. I examined the whole of the 14 vehicles of the excursion train before they left Dundalk on the morning of the 12th. The van which was destroyed was No. 250. It had six open wheels, and a hand-brake working two blocks on each of the outside wheels. The blocks were also connected with the vacuum brake. I think the van weighed 11 tons. About a week or 10 days before this, I had examined the blocks on the van, and they were in good working order. I could not take up a hole to increase their efficiency. The van had made one run after this. I next saw the van on the excursion train at Dundalk, and saw that the blocks were skidding for a distance of about 80 yards along the down platform. The brake had been put on by the watchman, and had not yet been released by guard Henry when I noticed it skidding. This was the last time I saw the van. When at Armagh, on the 21st, I saw the carriage examiner there and he said that when he saw the excursion train with a strange driver, fireman, and guard, he jumped into No. 250 van to try the brake, and found the brake in perfect working order, and that the van did not move when two or three shunts were made against it. The frames of No. 250 van and of the two vehicles in front of it were sound. 14. William Pearson, carriage examiner ; 11 years in the service, 5½ years examiner under the locomotive department, and 3½ years at Armagh : I saw the excursion train on Wednesday 12th June, and examined all the carriages and the two vans, and found them all right. I got into the front van a short time after, the empty train arrived here, and put the brake on. I found it acted properly when I put it on. When the train was formed to go to Warrenpoint, this ran was in the rear. I saw driver McGrath set back against the carriages to get over the points into the Newry yard, and I noticed the buffer-rods went in at the front of the train, showing that the brake of the van was holding. I was at the front of the train near the engine when he did this. 15. William Fenton foreman of running shed at Dundalk Junction ; 28 years' service, 11 years foreman of running sheds. I have been two and half years in my present position. On the 11th June I was acting for Mr. Park during his absence from Dundalk ; Mr. Clifford was the next in position to Mr. Park, but it being a shop holiday, the shops and offices were closed, and he was away ; and it was a recognised thing that I took the duty. At about 11 a.m. I was told by the running shed fitter that an excursion train was to run on the following day from Armagh to Warrenpoint and back, and I sent him to Mr. Cowan's office to get the instructions with regard to the train and number of carriages of which the train was to consist. He was told that there were to be 10 third class carriages, 1 composite carriage, and 2 brake vans ; 13 in all. I had already told Driver McGrath he was to take the train, having no other man for duty, and he made no objection in any way, and I was not aware he was not well acquainted with the road. About the same time (11 a.m.) I selected No. 86 engine for the excursion train, this being the usual engine employed for such purposes, and I had no doubt whatever about its being able to take the train of 13 vehicles over the Newry and Armagh line. I did not know the line myself but I knew that a similar excursion train, consisting of 14 vehicles, two years previously with Driver Beattie. McGrath having made no objection whatever, left me to think he knew the road well. I have always had an idea that one of the brakes must have been meddled with in the ascent of the bank. I saw McGrath about 5.15 p.m. on the 11th, and I asked him if he had all his tools, &c. ready for the special train next morning, and he said “ Yes.” Driver Murphy recalled : About 10 o'clock shunter Hutchinson came to me and said I should have to put the excursion train over the bank. I asked who sent him, and he said the station-master, upon which I said " all right." I was prepared to do this, but when the excursion train was ready to start, I got another message from the shunter that I was not wanted; and shortly after the station-master told me the same thing. If No. 86 engine had failed, I would have taken the train up with my own engine if there had been no assistance to be got at the station, but I should have asked for help if it had been possible to get it. On consideration, I remember that there were light whiffs of rain about the time when the collision took place. Driver McGrath recalled, after witnessing the running of the experimental train on the 22nd June : Supposing the weight of the train in to-day's Dan- experiment was the same as on the 12th, the only reason I can give for the engine to-day being able to get over the bank is that the engine was steaming somewhat better. In the yard, just after starting, the engine slipped a couple of times ; but after this it did not slip at all. The rails were perfectly dry where I stopped on the bank. I knew it was no use trying to start again after stopping. The use of sand would have been rather adverse to starting than otherwise, as the engine had not been slipping. After stopping I applied the vacuum brake, getting a vacuum of between five and six inches, and kept it on until Moorhead uncoupled the brake pipe. I then put it on again before starting,and release it to start when told to do so by Moorhead. In starting I did not slack back as much as was done to-day at the experiment. My fireman kept firing as we ascended the bank. I kept my engine in full forward gear all the way up the bank. There has been a slight shower before I started, but the heat of the rails had soon dried the effects of it. On starting, the steam pressure was 130 lbs. (8.963 bar), and was 125 lbs. (8.618 bar) when we stopped. Nothing passed between Mr. Elliott and me about waiting for the regular train to help us over the bank. After, in the first instance, stating that the 15 vehicles would be too much for my engine to take up the bank, I, after further consideration and talking the matter over with Mr. Elliott, consented to take them. I commenced following the runaway vehicles after they had gone 100 yards, opening my whistle as soon as I started, and keeping it open for a considerable time. I again opened it when entering the cutting before reaching the level crossing, where I was stopped by the gateman. |

| C O N C L U S I O N |

|

The above being the evidence taken by me in connection with this most appalling collision, I will now proceed with the aid of this evidence, of the personal investigation made on the spot, and of any further facts brought out at the coroner's inquest and magisterial inquiry, to give a brief history of the circumstances attending it, to endeavour to assign the degree of culpability which attaches to the various parties concerned, and to point out the means which might be adopted to guard, as far as possible, against the recurrence of any such catastrophe.